Unmistakable for its size, its long neck and legs and its characteristic bulging bill, in addition to the pinkish hue which becomes more intense on the wings, neck and legs with age.

Species 1

Greater Flamingo

Scientific name

Family 2

Taxonomic Affinity Group 3

Phenology 4

It is an “endangered” species resident in the Iberian Peninsula, it has a “metapopulation”, present over a large area, but interconnected, so that all the nuclei are very important. One of the largest nesting colonies in the Mediterranean (possibly the second largest) and by far the largest in Spain is relatively close to the salt flats of Roquetas, it is the ‘Fuente de Piedra’ lagoon in Malaga. Therefore, our salt flats play a particularly important role for the species during reproduction. This is reflected in the summer months (July to August) when up to two thousand individuals can be counted in our wetlands.

It tried unsuccessfully to nest in the salt marshes during 2012 and can be observed throughout the year.

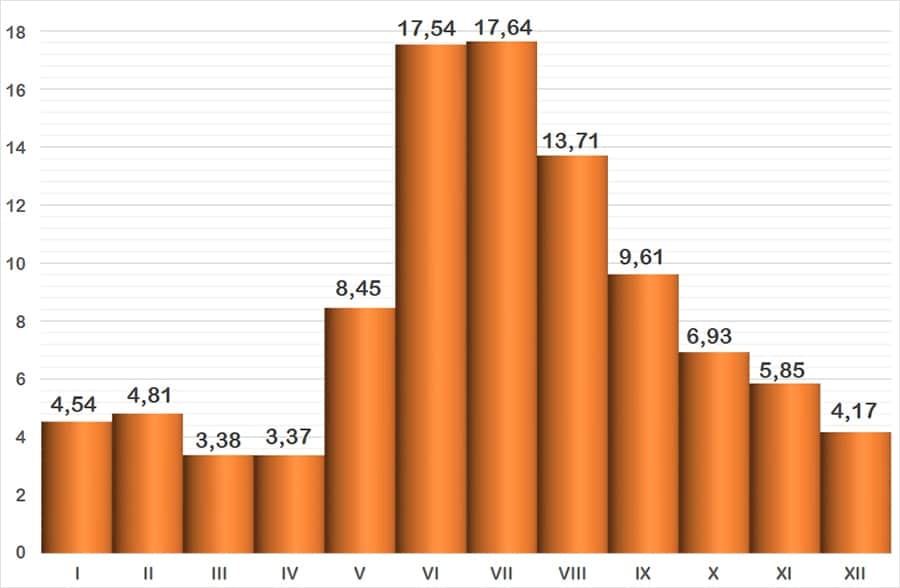

The graph represents the probability of seeing a species during the year, grouped into months. The vertical axis indicates the percentage value. Each of the bars expresses its value. The horizontal axis represents the months: I = January, II = February, III = March, IV = April, V = May, VI = June, VII = July, VIII = August, IX = September, X = October, XI = November and XII = December.

Observation recommendations

Whether in the shallow pools of the ‘Salinas Nuevas’, or in the deep pools of the ‘Salinas Viejas’, it is possible to see the flamingos feeding. They are even present in some of the smaller pools of “Cerrillos”, in the shallowest ones. It is possible to observe it from the beach when it moves around the bay of Almeria, especially during the last hours of the summer sunset.

Observation areas where we can find it

Notes

[1] The names used are from the list of birds of Spain, drawn up by SEO/BirdLife and updated to 2019 (https://seo.org/listaavesdeespana/). The reference is: Rouco, M., Copete, J. L., De Juana, E., Gil-Velasco, M., Lorenzo, J. A., Martín, M., Milá, B., Molina, B. & Santos, D. M. 2019. Checklist of the birds of Spain. 2019 edition. SEO/BirdLife. Madrid.

[2] The taxonomic family to which it belongs is indicated.

[3] Traditionally, waterbirds have been grouped according to their taxonomy or “taxonomic affinity”, i.e., when some birds coincide in certain features that allow them to be classified scientifically, but without leaving the rigour of science, they are put together in these groups so that they can be easily recognised. These groups are the following: Greves (belonging to the Podicipedae family), Herons and Similar (includes the families: Ardeidae -Herons- Ciconiidae -Storks- and Threskiornithidae -Ibises and spoonbills-), Ducks (the whole Anatidae family), Coots and Similar (the family Rallidae corresponding to Rails, Gallinules and Coots), Cranes (also with only one family, the Gruidae), Waders , a heterogeneous group, the most diverse of this classification, includes the families Burhinidae (Stone-curlews), Haematopodidae (Oystercather), Recurvirostridade (Avocets and Stilts), Glareolidae (Pranticole), Charadriidadea (Plovers), Scolapacidae and finally Gulls and Similar (the recently unified family Laridae, i.e. Gulls and Terns).

[4] Phenology studies the relationship between the cycles of living beings and meteorological factors, and in our latitude these factors manifest themselves as variations throughout the year, thus relating the seasons to the birds’ cycles (breeding, migratory journeys, etc.) The graph shows the probability of seeing a bird depending on the month. It uses data from 48 bird censuses carried out between October 2016 and September 2018. The method used is that of a census route with sampling stations, with a total count on the sheet of water.