Stubby in appearance, it can be confused with the Little Plover, from which it can be clearly distinguished in flight by the white stripe on the wings and black tips. It has a white body except for the back and upper part of the wings, which are greyish brown. The head pattern is also different to its relative the Little Plover too. It has a full and wider black collar on the breast, and the stripe on the forehead is also wider. The eye ring, although yellowish, is hardly visible. The female does not have this complete eye-ring pattern, and the black is replaced by dark brown feathers like those of the hood. In summer, its beak and legs are orange, the former with a black tip. In winter, the pattern becomes blurred, disappearing the black on the forehead disappears but a differentiating group of feathers over the eye like a long eyebrow remain, at this time the legs also become less striking.

Species 1

Common Ringed Plover

Scientific name

Family 2

Taxonomic Affinity Group 3

Phenology 4

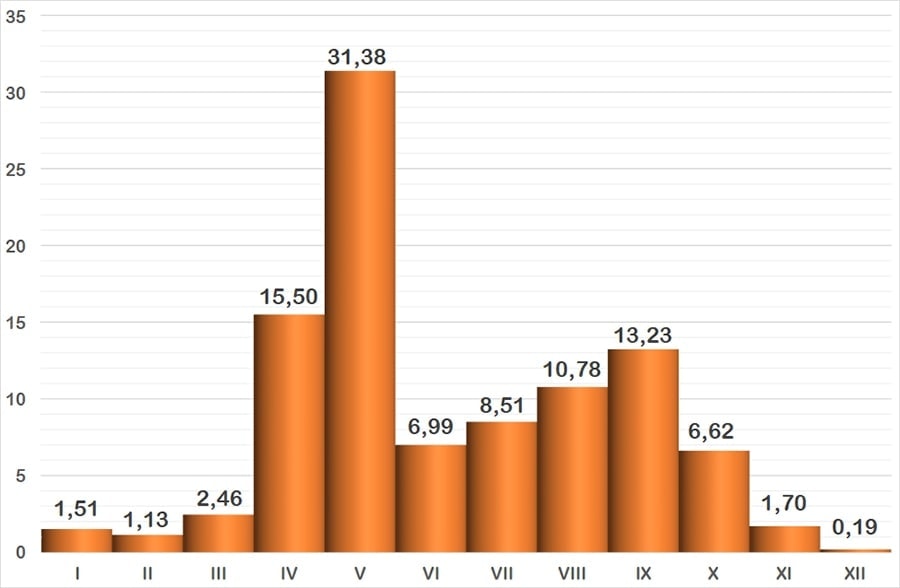

It is present throughout the year, although in winter it is less common, and sightings are therefore less frequent. It becomes noticeable during the prenuptial migratory passage and remains during the summer. There is an increase in sightings coinciding with the postnuptial passage. It does not reproduce on the Iberian Peninsula.

The graph represents the probability of seeing a species during the year, grouped into months. The vertical axis indicates the percentage value. Each of the bars expresses its value. The horizontal axis represents the months: I = January, II = February, III = March, IV = April, V = May, VI = June, VII = July, VIII = August, IX = September, X = October, XI = November and XII = December.

Observation recommendations

It is easy to watch wading in uncrowded areas and even in apparently dry areas, where there is residual humidity, and the soil abounds with the numerous insects that make up their diet.

Observation areas where we can find it

Notes

[1] The names used are from the list of birds of Spain, drawn up by SEO/BirdLife and updated to 2019 (https://seo.org/listaavesdeespana/). The reference is: Rouco, M., Copete, J. L., De Juana, E., Gil-Velasco, M., Lorenzo, J. A., Martín, M., Milá, B., Molina, B. & Santos, D. M. 2019. Checklist of the birds of Spain. 2019 edition. SEO/BirdLife. Madrid.

[2] The taxonomic family to which it belongs is indicated.

[3] Traditionally, waterbirds have been grouped according to their taxonomy or “taxonomic affinity”, i.e., when some birds coincide in certain features that allow them to be classified scientifically, but without leaving the rigour of science, they are put together in these groups so that they can be easily recognised. These groups are the following: Greves (belonging to the Podicipedae family), Herons and Similar (includes the families: Ardeidae -Herons- Ciconiidae -Storks- and Threskiornithidae -Ibises and spoonbills-), Ducks (the whole Anatidae family), Coots and Similar (the family Rallidae corresponding to Rails, Gallinules and Coots), Cranes (also with only one family, the Gruidae), Waders , a heterogeneous group, the most diverse of this classification, includes the families Burhinidae (Stone-curlews), Haematopodidae (Oystercather), Recurvirostridade (Avocets and Stilts), Glareolidae (Pranticole), Charadriidadea (Plovers), Scolapacidae and finally Gulls and Similar (the recently unified family Laridae, i.e. Gulls and Terns).

[4] Phenology studies the relationship between the cycles of living beings and meteorological factors, and in our latitude these factors manifest themselves as variations throughout the year, thus relating the seasons to the birds’ cycles (breeding, migratory journeys, etc.) The graph shows the probability of seeing a bird depending on the month. It uses data from 48 bird censuses carried out between October 2016 and September 2018. The method used is that of a census route with sampling stations, with a total count on the sheet of water.